|

Q: Charles Seville of Fitch Ratings to

economist L. Summers

I just

p style="border: 0px; font-family: raleway, sans-serif; font-size: 0.9em; font-style: inherit; font-weight: 400; margin: 0px 0px 30px; outline: 0px; padding: 0px; vertical-align: baseline; clear: both; line-height: 1.3em; color: rgb(0, 0, 0); text-transform: none;" align="left">

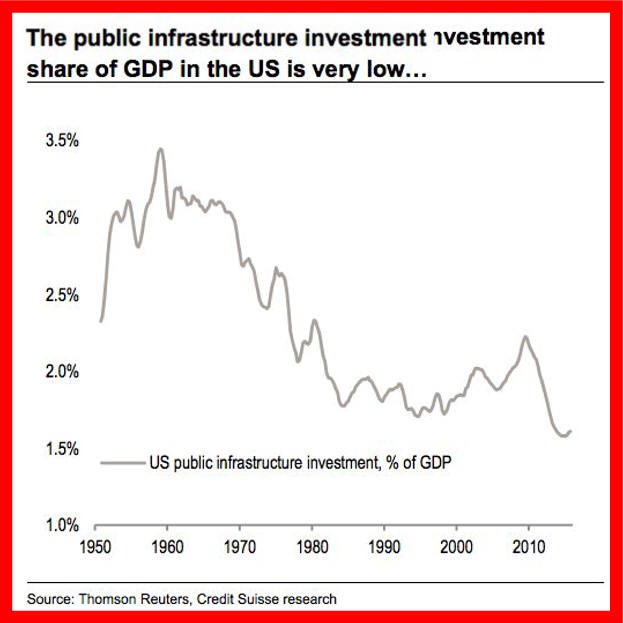

SUMMERS : Look, there are hard questions and

there are relatively easy questions. If you have a

country that can borrow money for 30 years at below 3

percent in a currency it prints itself, with epically

construction unemployment and record low materials

costs, it is an astonishingly bad idea to have the

lowest level of net infrastructure investment in 60

years relative to income.

Look at the cost of borrowing, and look at LaGuardia

Airport. (Laughter.) Look at the cost of borrowing, and

look at an air traffic control system where oak tag

bulletin boards and yellow stickier play a crucial role

in guiding your flight to landing. So the first and most

obvious thing to say is that there has been no better

time to stimulate demand in the short run, supply in the

long run, and to remove burdens from our children in the

form of deferred maintenance through a major program of

renewing the country’s infrastructure.

That’s not just a public sector concern. That’s a

private sector concern as well, which goes to—you know,

I make fun of the airports and all of that, but the

truth is that a phone call is more likely to be dropped

driving from LaGuardia into New York City than it is

driving from the Alma-Ata Airport into downtown

Kazakhstan. (Laughter.) And that’s about private

structure—private sector infrastructure investment,

which goes to a whole set of things in the regulatory

environment, in the incentives that are provided to

corporations.

Another example in the private sector is, has there

ever been a moment to put coal in our past—a better

moment to do that than now? That creates demand in the

short run, environmental improvement in the medium run,

and capital costs will never be lower. So that’s one

crucial part of, it seems to me, getting things going.

I think a recognition by the financial authorities

that if—that the problems used to be over-lending and

over-heating, but today’s problems are low-inflation and

lack of availability of credit for many in small- and

medium-sized business. And an orientation of financial

policy to that would move things—would surely move

things forward. There were lots of people who got loans

to buy houses in 2005 who should not have gotten loans

to buy houses in 2005. There are plenty of people today

who should be enabled to purchase a home, who have good

but not great credit, and who are not able to get access

to that capital. So I think the priorities have to

attach to stimulating public investment, stimulating

private investment.

And I would say on final—one final thing, an

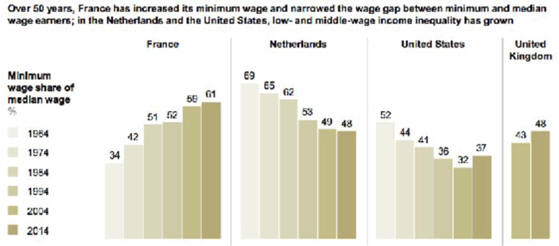

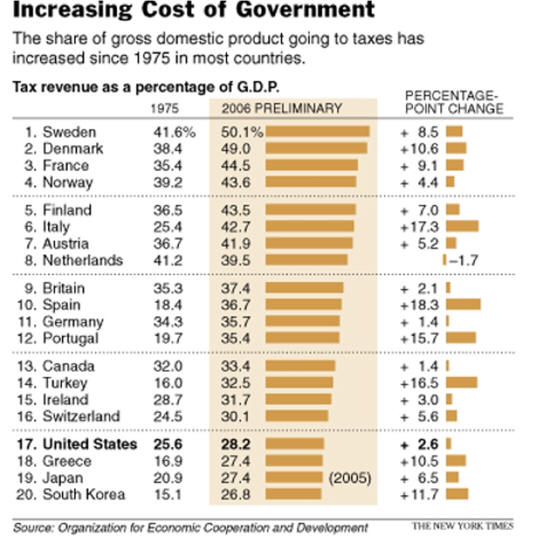

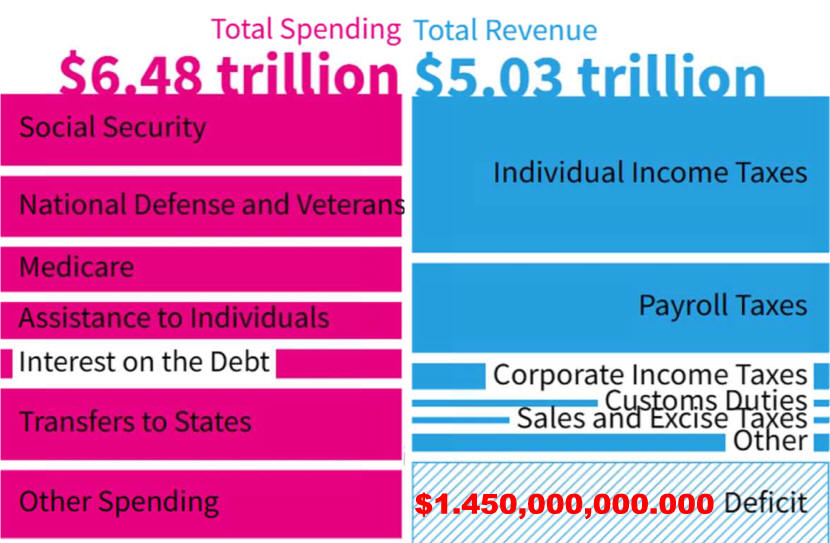

But at a time when the economy is short on demand,

the consistent trend towards income moving away from the

middle class is leading to more of it going to people

who don’t spend it, don’t inject it back into the

economy, don’t create demand, and that is contributing

to the sluggishness that is part of our problem. And so

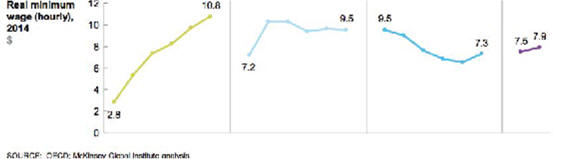

appropriately progressive taxation, a minimum wage that

was higher than the minimum wage when Ronald Reagan was

president—because we have made some economic progress

since then—and such measures would, I think, also

contribute to accelerating the growth rate of the

economy over the next decade.

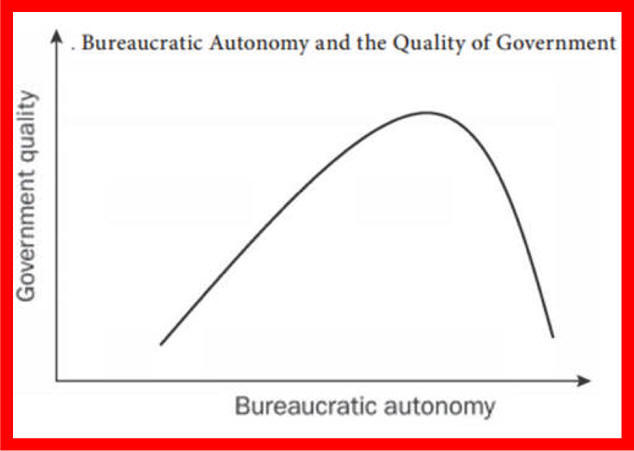

Glennon. In “National Security and Double Government,” he argues that while

congressional and White House control waxes and wanes,

America’s national-security apparatus is essentially set in

stone—a shadowy “second government” made up of mostly

nameless, faceless individuals who determine and administer

our policies.

In traditional representative government (the

people we vote for who are perceived to wield power) and

misrepresentative government (the people who actually move

all the key levers).

I think

this can be overdone, but I’ve come to think there’s

substantial truth in it. When I was a student, we—an

economics graduate student, 40 years ago—we were taught

about a fundamental tradeoff between equity and

efficiency, that you could make the economy more

equitable but in order to do that you’d have to have

more redistribution of various kinds and that would mean

higher taxes, it would mean that as people got benefits

you took more away when they got richer, and all that

created disincentives, and so you had to choose a good

place in the tradeoff between equity and efficiency. And

there’s still substantial truth in that idea with

respect to some policies.

He labels the first group “Madisonians”

after James Madison, who firmly believed that the checks and balances of our republic rest

ultimately on “civic virtue—an informed and engaged

electorate,” without which ”the governmental equilibrium of

power would face collapse.”

“Trumanites,” in homage to the president

who signed the 1947 National Security Act, thus creating the

security state as we know it today, including the Central

Intelligence Agency, the National Security Agency and the

Joint Chiefs of Staff. To run these complex organizations,

the Madisonians need experts, and the Trumanites are nothing

if not experts.

|

4The second group Trumanites determine

and implement the options put before the president. They

write and implement the bills that Congress signs and they

provide the classified justifications for the secret and

invasive policies that the courts defer to and uphold.

Intelligence Committee majority report on CIA interrogation

provides a rare and deeply troubling window into the “second

government” depicted in Mr. Glennon’s book

. According to the report, the Justice Department’s

Office of Legal Counsel defended the legality of the torture

program based largely on inaccurate information provided by

analysts at the CIA. Contractors hired to conduct the

interrogations were not given adequate background checks,

despite claims to that effect by the senior leadership. The

two psychologists hired by the CIA to “develop, operate and

assess” the program had no training in counterterrorism, no

specialized knowledge of al Qaeda or other terrorist

off organizations, and no on-the-ground experience as

interrogators—shortfalls that did not prevent the agency

from paying them a collective $81 million between 2005-09.

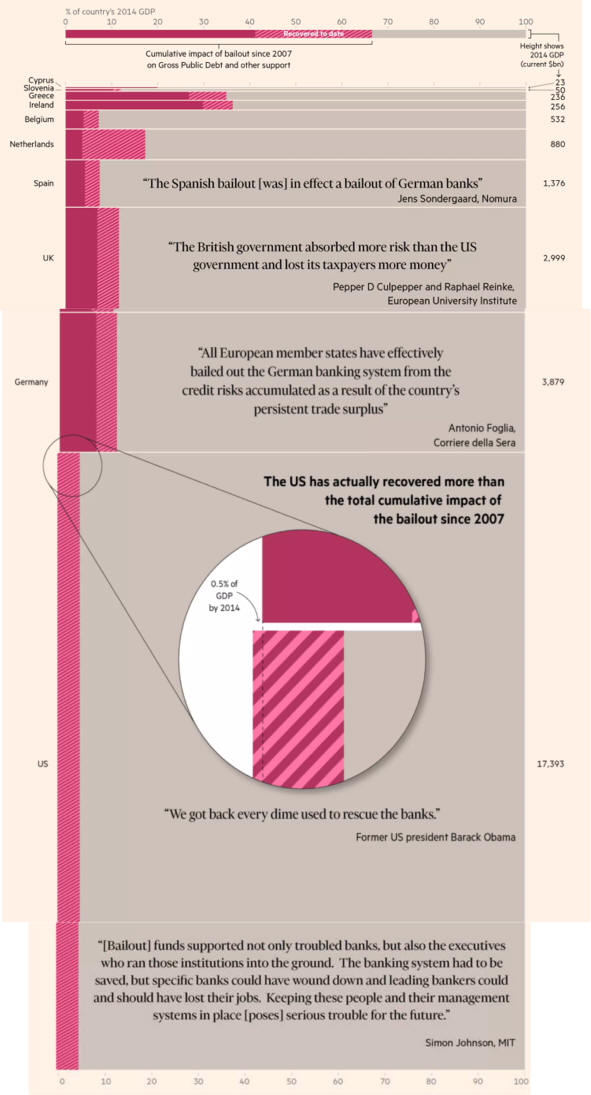

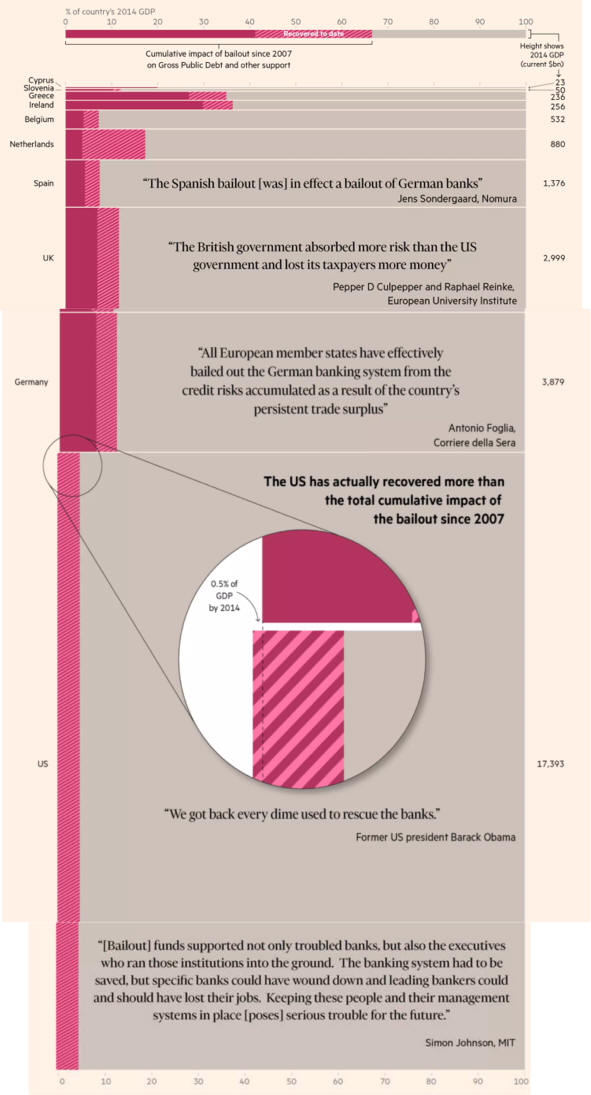

Interesting

discussion about European bank bailouts from the Financial

Times: The United Sates ostensibly broke even

on its bailout rescue of banks; European countries are

not likely to be as lucky.

bailout costs will burden years/ |